Parrot Girl

It was time for me to leave the orchestra

I see the parrot girl all the time

she looks at me

I turn away—I am shy

No parrot girl could make me lose my mind

though

Parrot girl puts on too much make-up

and in all the wrong places

One can tell a feathered wing did the work

Parrot girl says the same things over and over

Give me, love me, cater to my parrot needs

Parrot girl, she has a job

I’ve been to her place of work

She handed me plate with another feathered friend

fried and dried on it

Eat and enjoy she said

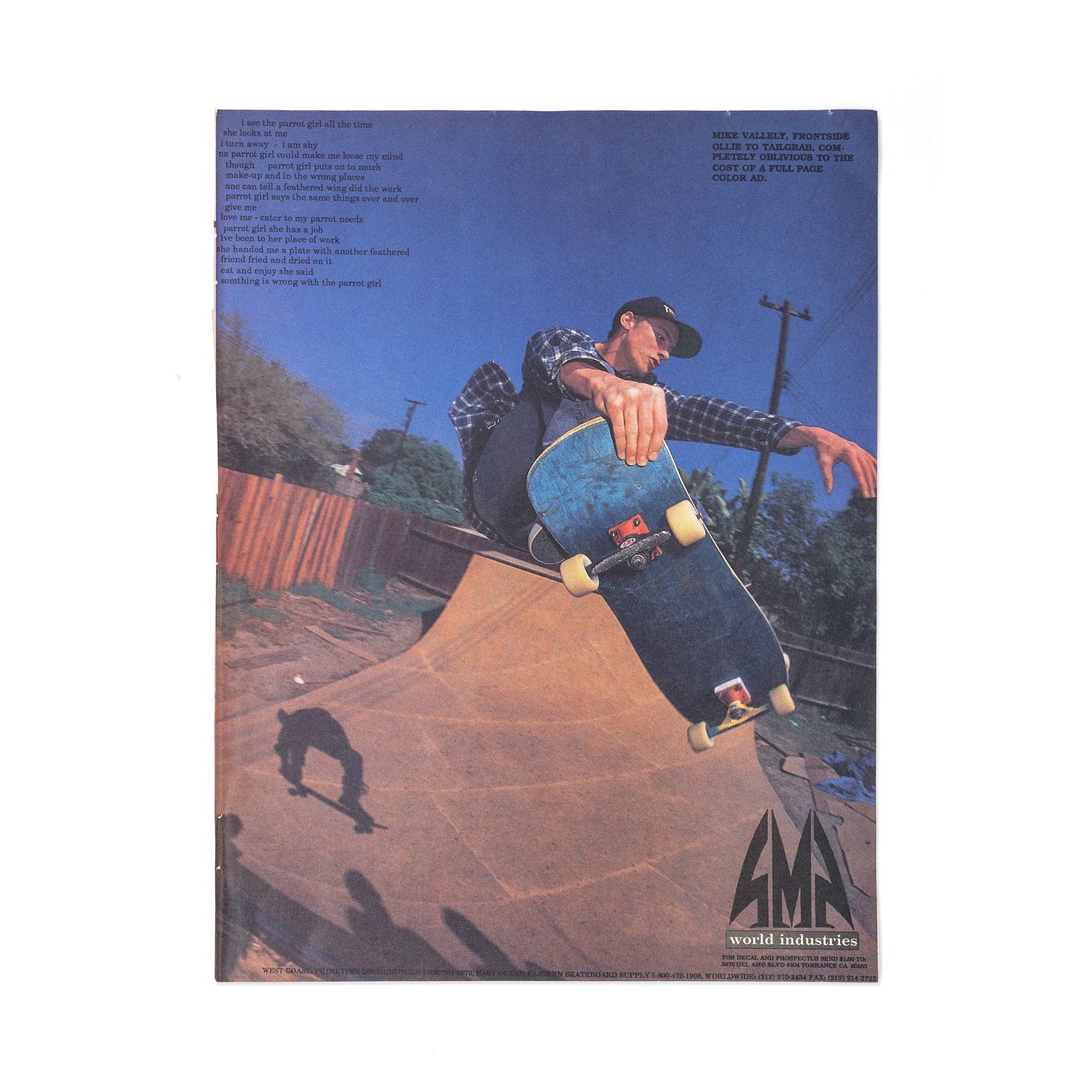

Something is wrong with the parrot girlParrot Girl stands as the very first poem I ever published. I insisted on its inclusion in my inaugural advertisement—marking the first-ever color ad for SMA World Industries, which later became simply World Industries—in the July 1989 issue of Thrasher Magazine. I wrote the poem while seated next to Jason Lee on an airplane headed to Sweden on March 20th of that same year. Just a month before, I had decisively walked out of a ten-year contract with Powell Peralta, the preeminent manufacturer in the skateboard industry, to become part-owner of SMA World Industries alongside Steve Rocco, Rodney Mullen, and Jesse Martinez. This was a bold move to sign on with a fledgling venture; many industry insiders thought it was career suicide.

Despite all the tears and talk, I understood precisely what I was doing and why. My decision to leave Powell Peralta had little to do with contracts, handbooks, graveyards, marketing campaigns, or any strained relationships with the company or the people involved. I have a profound admiration and respect for Fitz, Todd, George, and Stacy—those guys were instrumental in my start and believed in me. I truly appreciated everything they had done for me, especially Stacy—he was, and still is, one of my heroes. However, I envisioned a different path for myself and my skating—one that didn’t conform to the established mold. It was ultimately about my independence as a skater and as an artist.

I was brimming with my own ideas for advertisements, board shapes, graphics, videos, and more. Powell Peralta wasn’t and could never be my megaphone; at that point, I was just another skater on a bloated team, and I didn’t want to wait in line for anything. I was developing my own sound, my own style—it was time for me to leave the orchestra—blow solo—have solitary freedom. To me, skateboarding was about individuality—it had nothing to do with teams. Sure, someone had to manufacture the boards and sell them, but to me, those were my records—my songs. I wasn’t a trick or contest pony, and I couldn’t see a future in that environment unless I was constantly winning something. The rules of the game were not mine; I was leaving to create my own, becoming a law unto myself.

The entrenched skateboard market had become dullsville: slow-moving and predictable. My arrival on the scene three years earlier had been a cannon shot, signaling the opening engagement of the street skating revolution—and the follow-up bombardment was thundering. One of its leading combatants sat next to me on that airplane—bayonet fixed. I straddled a dangerous line between what was and what was becoming, refusing to throw my hat in with either camp.

Teaming up with longtime confidant Rocco gave me the opportunity to separate myself from the industry status quo, sidestep the hierarchy, and have a singular career. The dynamic with Rocco was different; we were creating something together. I wasn’t just another skater—I was an owner who could put one of my poems in an advertisement and do whatever I wanted. At Powell Peralta, I was under contract—a team rider, beholden to expectations I no longer felt I could meet.

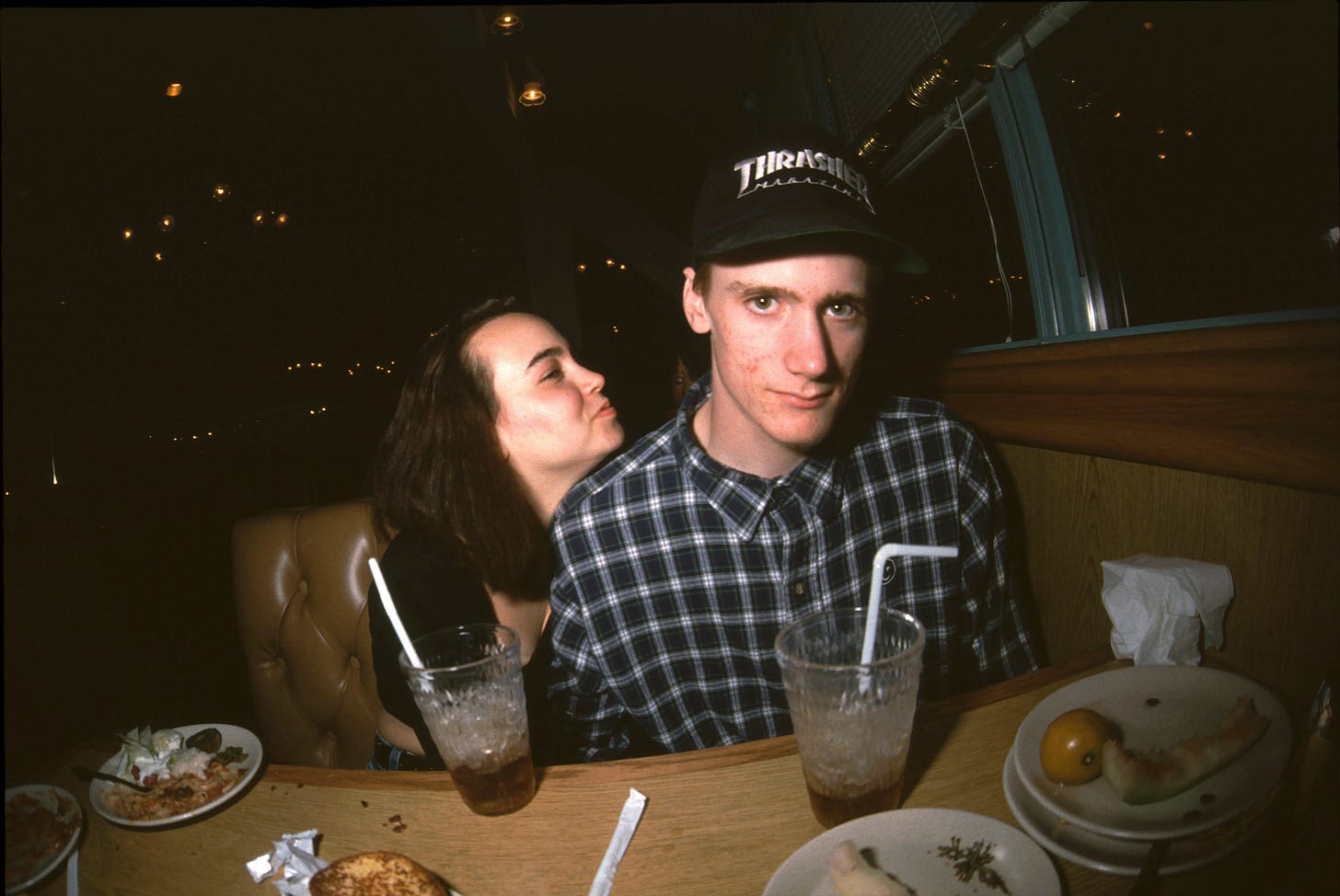

Two months before all of that went down, I had started dating Ann. The thing is, she had previously been in a relationship with Jason, the guy sitting next to me on the plane. Other people made more of a fuss about it than Jason. When it all went down, I went to Jason and talked to him—he was as cool as could be. As far as he was concerned, he had his rising skate career to focus on and he didn't want to get in the middle of what Ann and I felt was meant to be.

Despite the nasty rumors and gossip that floated around us, Jason and I remained friendly and continued to skate together. I talked to Jason on the phone a few days ago, and it was great to catch up. We’ve kept in touch periodically over the years. Now, thirty-six years later, Jason has built a legendary career in acting and skating, and he has a beautiful family. Ann and I have been together all this time and have two independent and successful adult daughters. No one is hung up about what happened way back when.

So, there we were, flying to Scandinavia for the first-ever World Industries promo-tour. I was already a veteran of the road, while this was Jason’s first time traveling overseas. We had just finished dinner when I took out my journal, and in an instant, the poem came to me—word for word, line by line. At that point in my life, writing had become an extension of my skating, and vice versa. To me, skating was always a form of physical poetry—physical graffiti; It was all about expression. I inscribed my poems onto streets and ramps with my board, and into notebooks and journals with my pen. This poem felt completely original, with a style that was a sort of poetic journal entry.

On our first morning in Sweden, we woke up early, feeling jetlagged. We were staying in a small economy cabin, which was situated up the road from the main full-service hotel. Stepping outside into the keen air, we were in desperate need of food—of something to drink. For that, we’d have to walk a half mile or so down the narrow street through the woods to the hotel.

Just then, we saw a bicycle propped up against a shed in the twilight. Jason ventured that the bike must be provided by the hotel for guests staying in the cabins, which seemed reasonable. So, we decided to use it. I climbed onto the handlebars while Jason pedaled us out of the gravel-strewn lot.

As we started down the road, Jason struggled to keep the bike upright and moving straight. We wobbled erratically from side to side, and with each crank of the chain, we nearly tipped over. About a quarter of the way down the hill, we realized the entire endeavor was futile—Fuck It. I jumped off the handlebars, and we ghost-rid the bike down the street, where it veered off the path into an overgrown ditch with a resounding crash.

At that moment, we spotted a family rounding the corner and coming up the hill, clearly shocked by what they had just witnessed—it was their bike we’d just jettisoned to oblivion. They ran over to see how they could recover it, as we rushed ahead with our heads down. Though we were ashamed of our behavior, we couldn’t help but laugh, and we laughed about it for days. We laugh about it still.

Back in the US, Rocco says he needs a photo of me for an advertisement in Thrasher. I produced the Ollie-Tailgrab at Scooter's ramp, captured by Christian Kline's lens. Then, I tell him I want to include one of my poems in the ad. Rocco responds with his signature mischievous giggle; you never know if he's laughing at you or is a co-conspirator. It doesn't matter either way; the poem goes into the ad.

When the ad came out in the magazine, people started talking—who is the Parrot Girl? Most assumed it was Ann—no fucking way. The last thing I wanted was to explain myself, my poetry, either then or now. But I was rankled by the presumption I had written something negative about my girlfriend in Thrasher. When I tried to convince anyone otherwise, they thought it was all evasion. One friend even went through the poem line by line, insisting it was obviously about Ann. I couldn't believe it; what seemed obvious to others and what was evident to me were two different realities. When I included the poem in the ad, I had no idea that anyone would read into it or care. But everything in my life then had taken on an air of controversy—it made it hard to breathe.

Rocco added a caption to the advertisement that highlighted my complete oblivion to the cost of a full-page color ad, and I was. When I joined World Industries, I had two stipulations: first, I wanted a guaranteed salary regardless of board royalties; at that time, most pros were only compensated with royalties from the sales of their signature products. Second, I insisted that the company upgrade from its low-quality black-and-white ads to full-page color ads.

From the start, my boards sold like crazy—salary demands were never an issue, but the color ads were quickly abandoned. More importantly, the Parrot Girl ad represented the first truly independent notes of my career. It served as a glorious announcement and set the tone for an original, individual approach to my life in professional skateboarding.

Thanks for reading!

Continuing to love the stories you share on here. Great info on your switch from Powell to world and your vision going forward. Also HELL YEAH the Rats are back! I’ll definitley be at the Chicago or StLouis show. See you there!

"Leaving the orchestra...blowing solo." Great analogy! Also, the picture of you and Ann really makes me miss Souplantation! Loved that place! 😄